Between Decisiveness and Discovery:

The Paintings of Harold Feist

Full disclosure: Harold Feist and I grew up together, professionally. We met about four decades ago, when I was a rookie curator with my first museum job and he was a young painter finding his own voice. We were both transplanted Americans working, for complicated reasons, in Western Canada, I at what was then the Edmonton Art Galley, now the Art Gallery of Alberta, he teaching in Calgary. We've been friends ever since, despite our living in different cities and even in different countries during most of the time we've known each other. Because of this history, I cannot pretend to be an objective observer of Feist's work – not that critical judgments are ever anything but subjective – but I can claim to be a particularly informed viewer, as a critic who has had the privilege of visiting the artist's studio regularly and who has watched his evolution with deep interest and engagement, over a long period.

For all of that time, during the many hours I've spent in Feist's studio, when we've looked at work and talked about everything from art to pets to our fathers' having both been stationed at Randolph Field, in San Antonio, Texas, I've been fascinated by the apparent contradictions embodied by the man and his work. Why? Because Feist's abstract paintings, with their subtly modulated surfaces and sensuous colour, whether intense or subtle, have usually seemed, at least at first viewing, to be the exuberant products of uncalculated intuition, while exuberance and abandon are among the last things we would attribute to the author of those paintings.

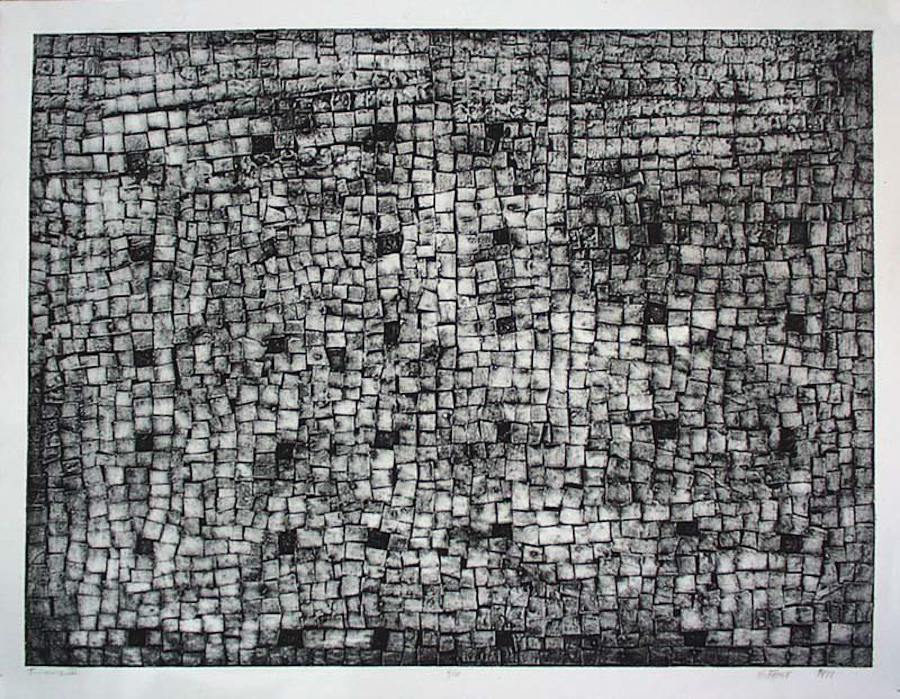

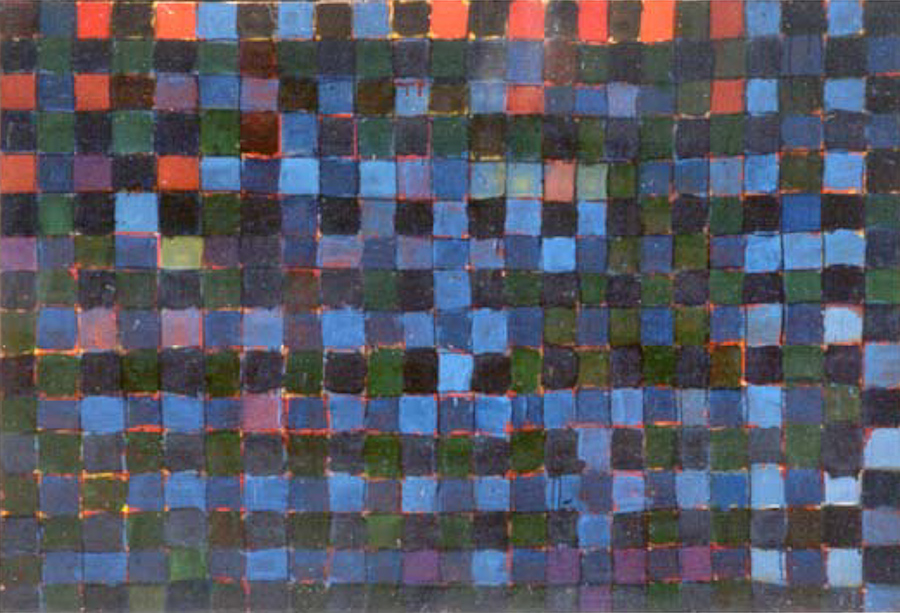

The works by Feist that I encountered, in the early 1970s, were wonky, over-scaled checkerboards made of strange purples and murky greens. They suggested an effort to achieve the spontaneity of children's art, despite their clear aesthetic ambition. In these, as it turns out, unforgettable pictures, the casual geometric grid that appeared to be their generating principle was almost overwhelmed by rough hewn, swiped brushmarks and wobbly drawing.

|

|

| Tamanus III, 1971, collograph,22 x 30" |

|

| Tamanus II, 1971, collograph, 22 x 30" |

|

|

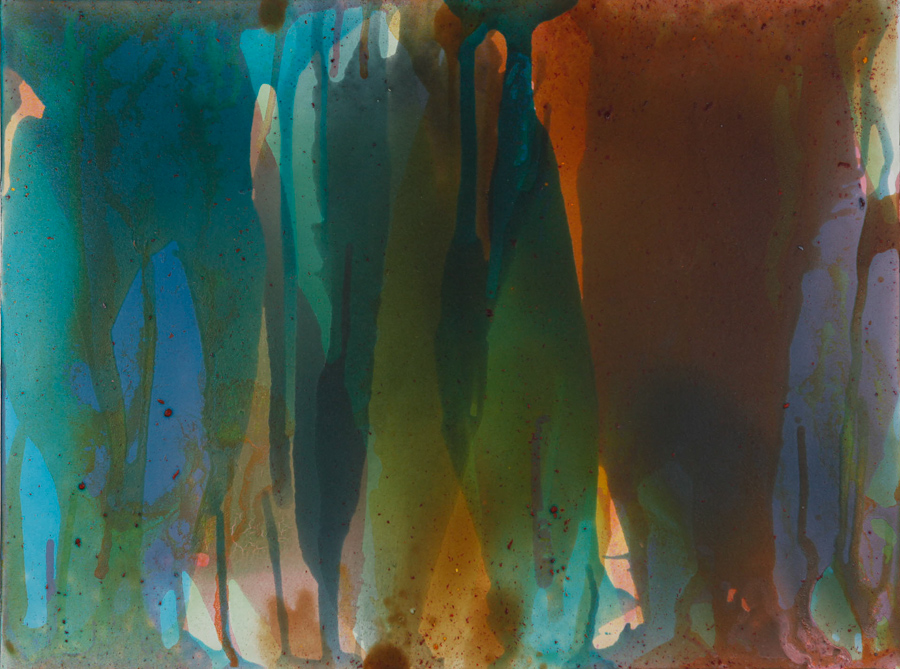

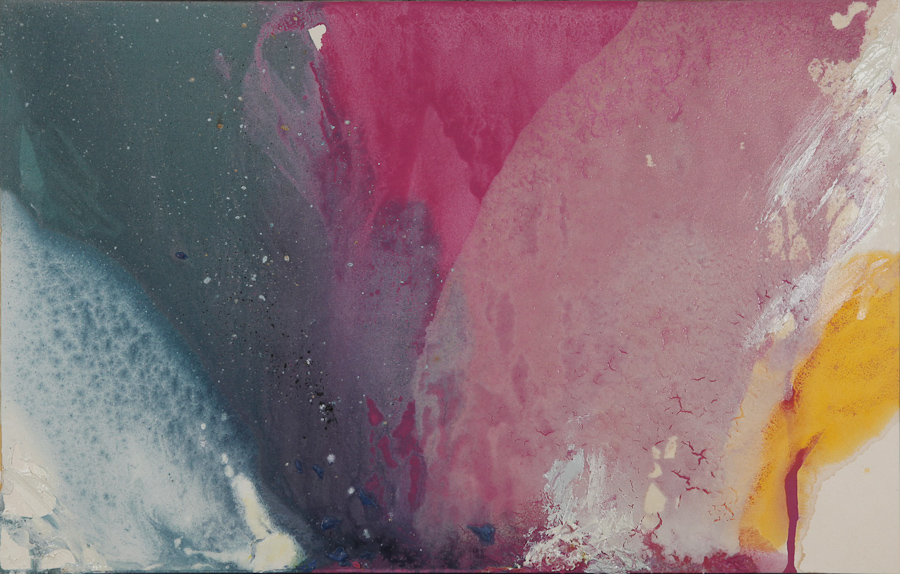

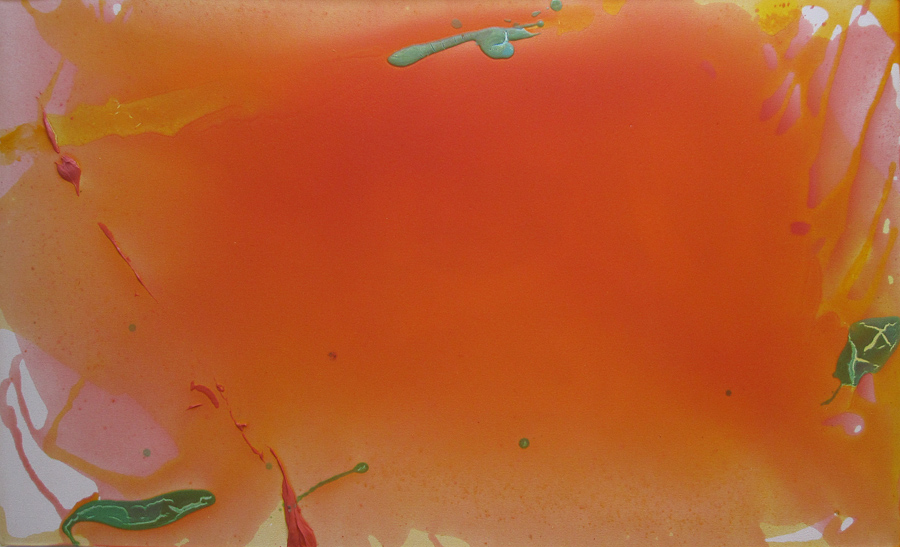

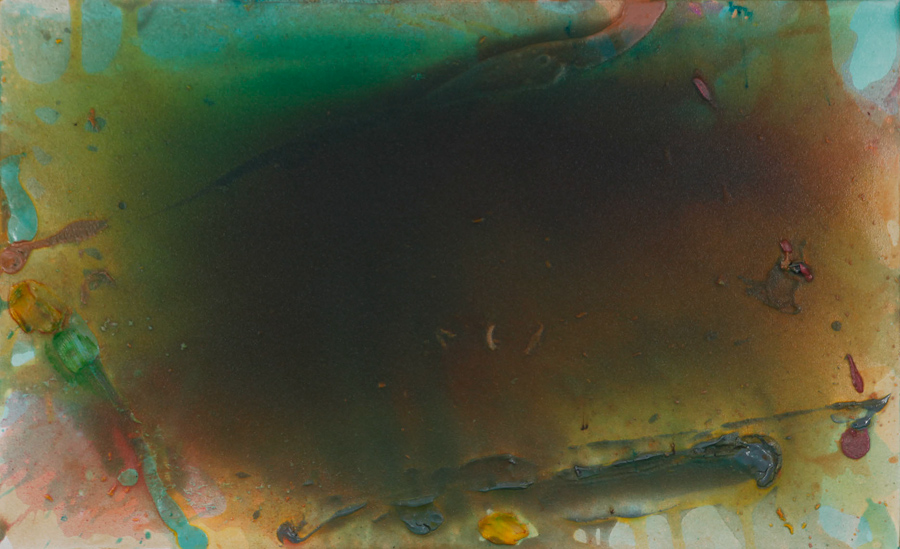

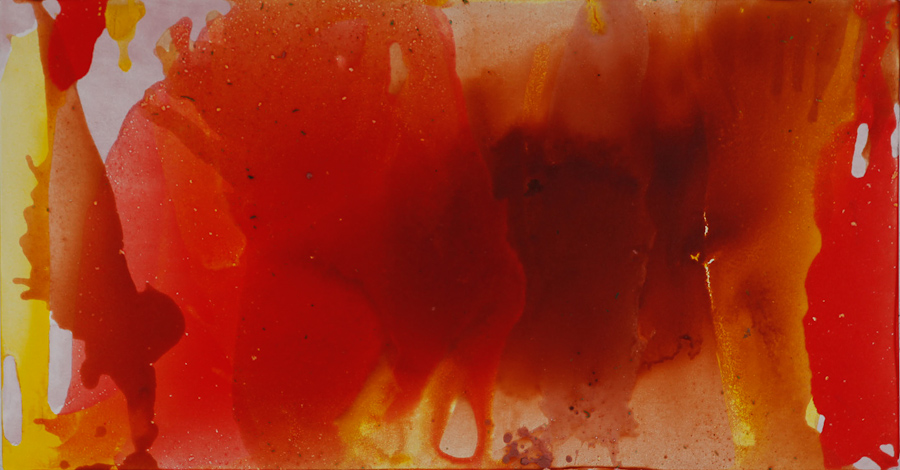

The most recent paintings I've seen in Feist's studio, in the summer of 2010, were luminous, elusive images built out of floods of radiant, transparent hues that seemed to have come into being almost without the agency of the hand, as if colour had magically spread across the canvas simply because the artist thought about its doing so. Yet just as in those early checkerboards, where order and chaos seemed to be engaged in a wrestling match, with time, Feist's recent lush, chromatic symphonies revealed the presence of underlying coherent rhythms and structures, like distant memories of the geometry that held together the casually brushed images that were my initial introduction to his work. These implicit rhythms and structures appeared to have mysteriously influenced the flow of colour across the canvas without inhibiting its freedom in any way, paradoxical as that may sound. They acted like a tidal pull that disciplined the layered pools of individual hues and urged their edges into loose parallels, like waves breaking on a beach, each with its own energy, each bringing its own flood of water, yet obedient to some dominant physical force. Yet unlike breaking waves, the liquid expanses of colour in Feist's recent paintings seemed to spread and swell rather slowly, as if finding their own way, rather than to racing across the canvas in response to a single strong directional impetus. The intricate flourishes and runs that often enliven the edges of the pools of colour seemed further to defy physical directives by heading off in unpredictable ventures of their own.

It seemed impossible to decide how these paintings were made – were they poured, thrown, or manipulated in some way? There appeared to have been some repeated action at the start of every one, but each pool of colour seemed only minimally influenced by its neighbors, whether it ran parallel to it or overlapped. I tried to decipher Feist's process from the visual evidence he left us, in his recent work, but I soon abandoned the pursuit, as I often had before, seduced by their chromatic sonorities and linear complexities. The unpredictable image and its emotional resonance ultimately trumped any considerations of process.

Yet my almost subliminal awareness of the orderly structure underlying the pools of color intensified my sensitivity to the "inexplicable" aspects of the recent paintings, as it has in the past. The subtle coexistence of apparently unfettered spontaneity and innate order, in fact, proves to be a constant over the years, throughout Feist's evolution. Yet though the Apollonian aspect of even his most Dionysian images almost always slowly but forcefully insists on being recognized, when we concentrate, their sense of the improvisatory and the unexpected always dominates. Feist's paintings are steadfastly about pure visual experience, consciously divorced from systems or theory. They resist explication, remaining wholly dependent upon the direct encounter with the materials and characteristics of painting itself. They speak eloquently, without inhibitions, about the evocative, associative power of colour and the materials of picture-making.

In contrast to these forthright, unguarded paintings, Feist, the man, is cerebral, reserved, rather shy, self-deprecating. He is notably well-read, with an impressive knowledge of scientific arcana and the cyber-world. I have learned, over the years, not to be surprised by the breadth and depth of my painter and sculptor friends' expertise, which can embrace everything from rodeo to hyper-refined French cooking, and much more, but Feist may be the only artist I've encountered who reads string theory for entertainment. He is someone, in other words, whom we might expect to make art that was systematic, theoretically based, emotionally withdrawn, and/or required programmatic verbal explication to yield its secrets Yet he has told me that early on, when he was still in art school, he made a deliberate decision to move in an entirely different direction in his art. Far from seeking verbal reinforcement for the visual, he courted the irrational and the anti-theoretical: "That meant I could turn off my logic when I worked and thus leave the door open for some other faculty to come through," he has said.

Many of the abstract painters whom Feist admires (and got to know), including Larry Poons, Kenneth Noland, and Jules Olitski, have frequently spoken of making similar efforts "to get out of their own way," as they have described it, in order to avoid relying on habit or expected solutions in the studio. Olitski often described what he considered to be the ideal state of mind in the studio, when he stopped worrying about what he was doing and gave himself over entirely to the experience of working. He liked to quote Pablo Picasso's saying "This is not what I sought, but it is what I found," about a painting he had just finished – an oblique encapsulation of the effort, by whatever means, to remain open to the unexpected, to avoid preconception and familiar solutions.

It hardly needs pointing out that this approach does not mean abdicating pictorial intelligence or striving for a kind of mindless manipulation of materials. Far from it. Olitski and his colleagues all arrived at procedures, such as working in series or adopting unlikely tools and methods that subverted conventional facility, in order to tap intuition, spontaneity, and personality – that is, to find ways that allowed them to work out of sheer informed talent with a minimum of calculation and plotting. Noland's decision, for example, in his celebrated Circles, to acknowledge the center of a square canvas and then deploy concentric bands of varying sizes, hues, and densities around that center, permitted him to forget about composition and concentrate on what he has said really interested him: the expressive possibilities of colour, interval, scale, and edges. The repeated (but infinitely variable) format of his equally celebrated Stripes, with their sensitively adjusted banks of parallel bands, had a similar effect.

Olitski's adoption of a commercial paint sprayer (and later, other industrial tools, including, at the end of his long life, leaf blowers) allowed him to realize his stated ambition of wanting his paintings to be airborne, disembodied visual experiences – or as he described it,"just a cloud of colour that remains there transfixed." But spraying paint also forced Olitski to think about composition in unprecedented ways and prevented him from relying on his virtuoso ability to draw. Decades earlier, Jackson Pollock used house paint, dripped, poured, and thrown with sticks, stirrers, and brush handles onto the canvas for similar ends, making expansive, all-over paintings that set a precedent for Olitski's sprays; it has been suggested that Pollock's pouring was a kind of "drawing in the air" that offered an extraordinary sense of liberation to an ambitious artist who was never a natural or accomplished draftsman, in conventional terms. Similarly, Helen Frankenthaler's stain method, which Morris Louis famously described as providing "a bridge between Pollock and what was possible" (and eagerly adopted) not only allowed her to preserve the expressive luminosity of colour, but also forced her to abdicate preconception and to respond to possibilities in that arose in the course of working. And so on.

The aims of all of these artists were identical. All sought procedures that would allow them to "get out of their own way" and to remain open to what could be found rather than what had been sought. Pollock, Frankenthaler, Olitski, and Louis adopted methods and created situations that eliminated control, in order to discover the unexpected, perhaps even the inconceivable. Noland worked from an opposite premise, but arrived at a similar result. By beginning every picture with a predetermined, repeatable and repeated structure (although endlessly variable within own limits) he managed to subvert control; the formal, considered structure of the painting became a given, allowing him to think about something else. Feist's approach could be considered as a combination of these two apparently opposed practices.

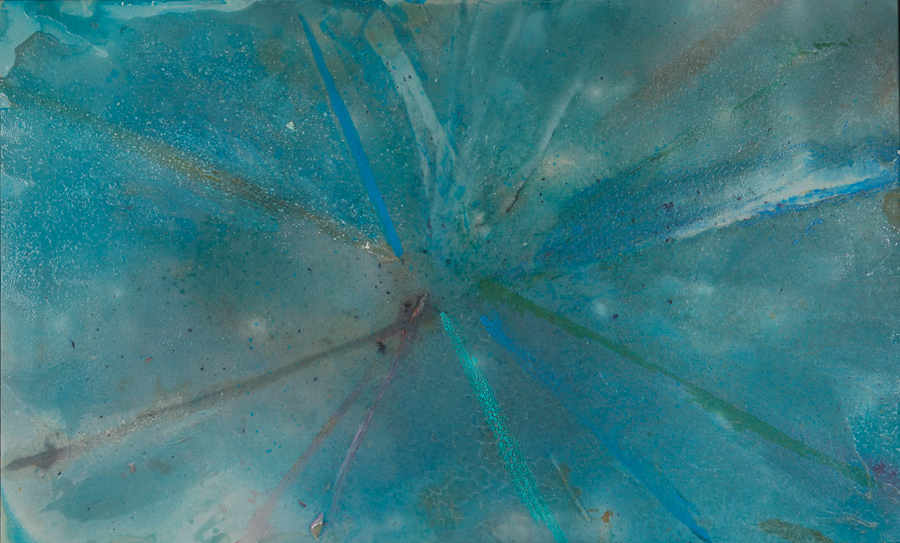

Feist admires Olitski's work enormously. The expansive, purely visual qualities of Olitski's signature Sprays of the 1960s and '70s and the voluptuous sensuality of his iridescent, lush paintings of the 1980s and '90s gave Feist permission to explore the territory that he has claimed in his fluid recent works. But many of Feist's earlier works can be described, as Noland's Circles and Stripes can, in terms of a generating rational structure: a spiral, a grid, radiating spokes. Yet like Noland's Circles or Stripes, that generating structure was neither an arbitrary decision nor, ultimately, what the painting was about. Instead, the seemingly neutral format, far from being an end in itself, has been a means of providing Feist with a kind of distraction from subject matter or related concerns, encouraging the arrival of "some other faculty," facilitating improvisation, and freeing him to make his work with deliberate spontaneity and passionate, engaged detachment, paradoxical as that may sound. As a result, no matter how disciplined the format, the "other faculty" that is allowed to come through is a kind of intuitive romanticism, a complete surrender to the emotional resonance of colour and surface relationships.

|

|

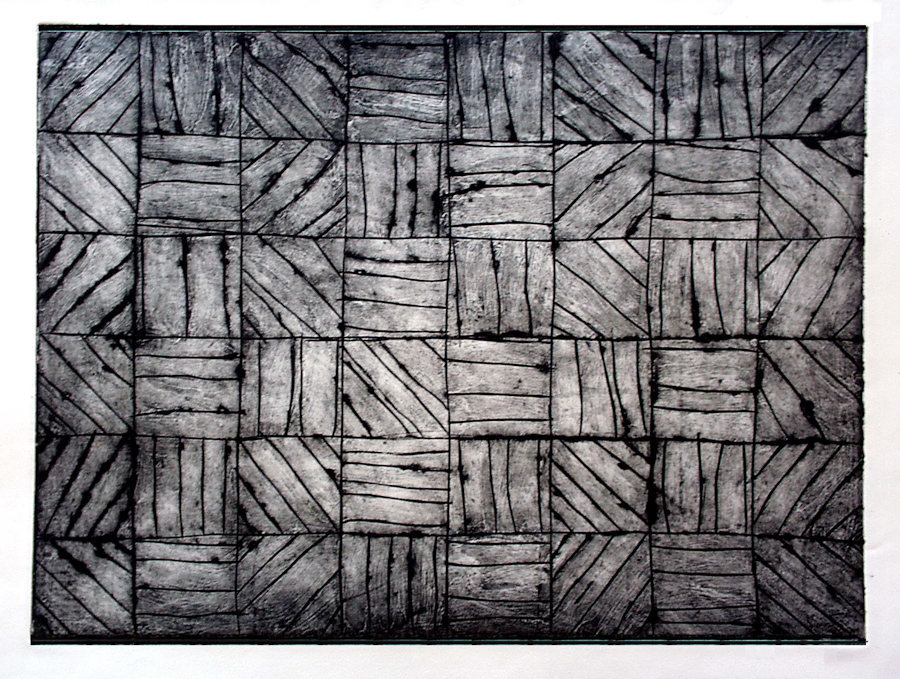

| Camposanto, 2009,49.5x37.5" |

|

Feist has described painting his first Spoke picture, in 1975, as "genuine eureka." Once he realized the worth of the simple, flexible format, he has said, "Paintings came one after the other like it was a matter of letting them loose..." It was obvious that they wanted to exist and should exist. My job was to get the paint right." As he continued to explore the potential of the Spoke image over the next years, "getting the paint right" took many forms. The first Spoke paintings were earthy near-monochromes but, while he continued to make subtle, tonal pictures with deliberately limited chromatic ranges, he also began to make Spokes that were riots of multiple colours. In the same way, the radial elements could be "passive" surface inflections or "active" carriers of hues. They could be wide or narrow, defined or blurred; they could be crisp strokes, assertive scrapes, or soft-edged gestures, and they could also vary in density and degrees of transparency. Scale could vary, as well as the implicit energy of the configuration – the speed or slowness of the implied spin – depending on the proportion of the canvas. The first Spokes were symmetrical and confrontational, so they seemed straightforward and the implied spin, controlled, even stately. Later Feist increased the tension in the image by elongating his canvases, compressing the spokes on the narrow sides and extending them on the long sides. This could produce a fleeting sense of three-dimensionality, a momentary recollection of how a round, radial configuration might appear in perspective, an illusion that was almost immediately cancelled by the fact of paint on a surface. The implied spin, in these elongated pictures, virtually came to a stand-still, as the disparities in the lengths of the spokes on various sides similarly forced us to think of them as marks on a surface rather than distillations of movement.

Feist thought of his radiating format as "dynamic and full of problems" but also as "simple and knowable…like bones or a skeleton," he has said. "Every body has a skeleton but the fleshing out can lead to anything from a Muhammed Ali to a Woody Allen." He liked the clarity and intelligibility of the radial structure. "The viewer could look at the picture, see the spokes, see that it all followed more or less a system, then maybe – having been enticed straight in through the front door – see the painting as a painting." As the Spoke paintings evolved, they became increasingly varied – which is not to say that they became any less clear or intelligible – as Feist explored the extreme limits of the givens of his chosen format, at the same time that he worked against them. The radial structure could shift away from center or the spokes themselves could all-but dissolve into pools of transparent color so soft and diaphanous that the radiating gestures that created them survived only as memories. Feist recalls his early realization that the Spoke format would permit him enormous scope and that he somehow owed to himself and to the paintings to see where their implicit possibilities would take him. "I don't think I had done but one or two before I vowed to myself to keep doing them for at least a year," he says. "Now I wonder how young I must have been to think a year was a meaningful length of time."

Feist kept his vow, then briefly abandoned the Spoke structure for a more minimal approach, employing wedge-shaped sections and pale, monochromes, and in 1978, returned to the Spokes with new enthusiasm and newly refreshed palette of full-throttle colour. Yet periodically since then, he has moved away from the Spoke format, sometimes for years at a time, to investigate the permutations of asymmetrical wedges or of grids of different degrees of order and scale, now strict, now loose; now oversized, now tightly packed; now severely frontal, now tipped on end. At first encounter, the radiant, fluid images Feist has made since 2009 seem to represent another of those departures. They seem to belong to a family far removed from the radiating format and to have been driven by a very different set of assumptions than those that generated and sustained the Spokes. Rather than reading as responses to a deliberate, willful series of gestures, as the Spokes do, Feist's pictures of the last few years seem to have come about as inevitable manifestations of the nature of his materials. They appear to be about the physical properties of liquid pigment, about the fact that paint flows, runs, spreads, and pools. Overlaps and bleeds are made into eloquent chromatic events, like the "colouristic" overtones of chords, unexpected alterations in the relationships of hue announced by the larger pools of thinned-out paint. Edges and rivulets are made to function as complex drawing, as small, finely textured incidents that, like the details of traditional illusionistic paintings, engage the eye at a different, more intimate scale than the large sheets of glowing colour. It's as if Feist had coopted gravity itself as a painting (or drawing) tool, rather than imposing his hand and desire on his material. Yet at the same time, the floods of colour seem to have been directed by sheer insistence, by the force of pictorial intelligence and personality.

|

|

| Superposition, 2003, 48.5x33" |

|

| Barrier Reef, 1997, 58.5 x 60" |

|