A Commentary by Harold Feist

I have been a fan of Doug Haynes' work and of Doug, the artist, for a long time now, and for the greater part of that time I've had the good fortune to have him as a friend. It is, however, a somewhat curious friendship in that it started through our work and advanced considerably before either of us knew it was there. Art comes from art, as it’s said, and art talks to art - like a jungle telegraph. Things float in the air that artists breathe in (inspire), and work from, even when the studios are separated by thousands of miles, as ours happen to be. Geography is mostly physical, while art is that, plus something else.

Art has something that's alive and living on its own terms. The thread of tradition as it is picked up by each generation makes a lot of that necessary. We artists look back to, and admire, the same masters, and follow the links from the past forward in time, right up through those who were working only yesterday, and those who are at it today. Naturally, we find ourselves converging towards a single path that has been trodden for us leading off towards quality. That is where it will lead us if our eyes are true, our minds are open, our hearts have the capacity for wonder, and -- to understate it -- if we are up to it.

The optic nerve doesn't just run like a wire back to the brain but seems to have connections and stations all through us. You can be moved down to your toes by something you see in a work. Everyone knows this. I have stood shoulder to shoulder with Doug in more than a few museums and galleries over the years, looking at works by everybody under the sun, and time after time we have had it confirmed that we were both seeing and feeling the same thing alive there before us.

It is said that nothing is so debilitating as total freedom — that when faced with an endless array of choices or directions, the normal human response is to freeze up and sink deep ruts into the mire. If the coin were to be flipped, would it then be true to say that nothing is as empowering to the individual as constraint — that when strongly fettered, bound up, under the thumb, the normal response is to bridle against it, to wriggle around, to burst and break free with frustration, perhaps even passion? Inmates in prisons have been known to pick away at cement walls with spoons for years on end, or build replicas of great ships out of match sticks, or transport themselves out of their cells with poetry or fiction or learning. A case might be made for defining a person by what they have fought against or have managed to accomplish in spite of their circumstances — or even in spite of themselves.

In the case of this series of paintings we can look at El Greco as the liberating constraint and source of Doug's inspiration: the "thumb" he wants to be under. Is it arrogance to follow after a master, trying to do something of the kind? Any work of art requires something akin to arrogance on the part of the artist since it is made within a tradition and, therefore, has to fly in the face of the best that has been produced. Without arrogance, without ignoring the impossiblity, without foolhardiness, or without some small amount bravery, who could expect to accomplish anything at all in such an arena? All artists must come to terms with this and most must be pitied for it. The wise thing might be to not even try, but to live a life content with looking at all the magic that has been brought into the world by those before us, and leave it at that — to just enjoy the experience of all of it. But some see, then want to do, are compelled to do — and to do it as well as they have seen it done. The odds against aiming at that level are overwhelming but still they (we) try. Is it courage? More bone-headed-ness, probably. The thicker the bone the safer the brain inside? Not if most of the battering is self-induced, the brain bouncing around inside the skull tossed by tides of doubt, fear, reality. The person vs. the artist. The first flesh and bone: the second an idea -- the “I." These don't always live well together inside one head. Doug's paintings are in homage to an old master but are, as well, a reiteration of pictorial devices and concerns — narration, figuration, even such things as angels! — that have not, so far as I know, been dealt with in such a direct manner and to such great an extent as in The Toledo Series. This kind of intent is new to abstraction. It is a hybrid of modernist, non-objective painting and the kind of painting that makes use of subject matter. Shapes flutter and dance as if they are putti or cherubs or angels ascending and floating within a shallow, dished-in space -- within a stage or niche set in the wall. There is a richness and intensity of colour, and a deeper, more sonorous surface than was there before in Doug's work. The same hand is there, but it has more of a Midas touch now — opulent, sensuous. Doug has managed to tap into a new resonance by following the lead of this experience of looking at El Greco, his El Greco. That is, finally, what we are looking at — his vision.

Harold Feist, Toronto 1991

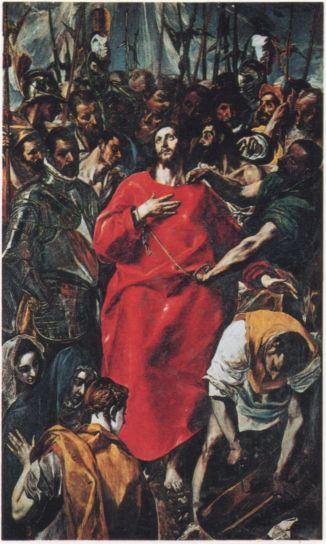

El Greco

El Espolio (Disrobing of Christ), c. 1577 - 79

oil on canvas 112” x 68.1"

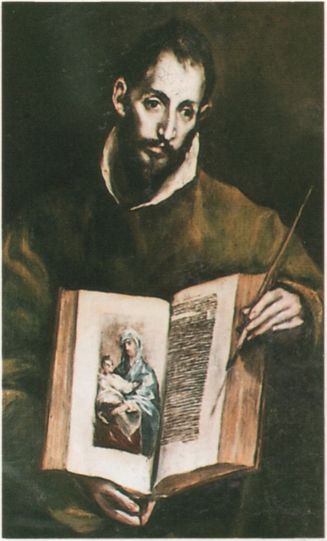

El Greco

San Lucas c. 1605-10

oil on canvas 39 x 29"

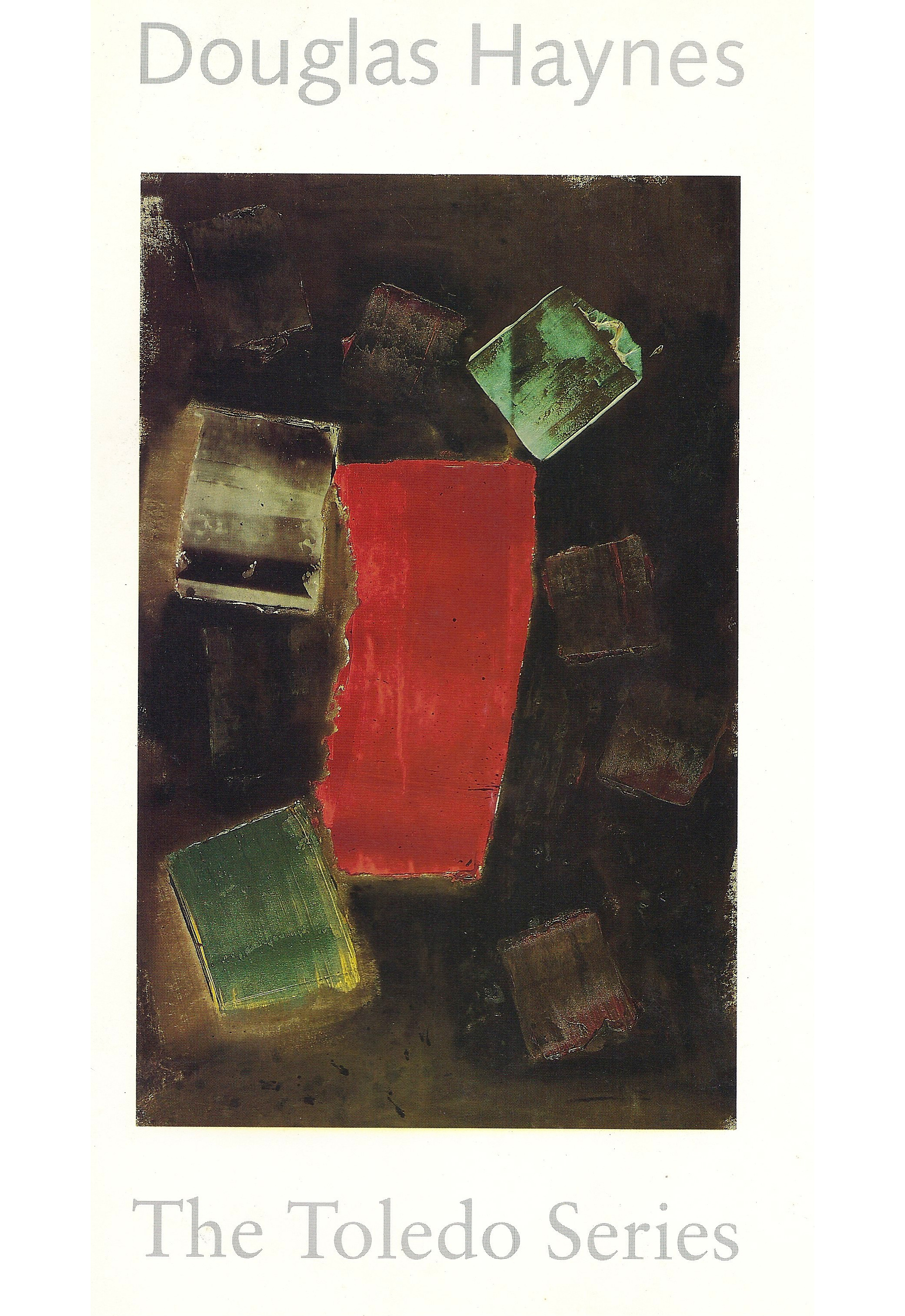

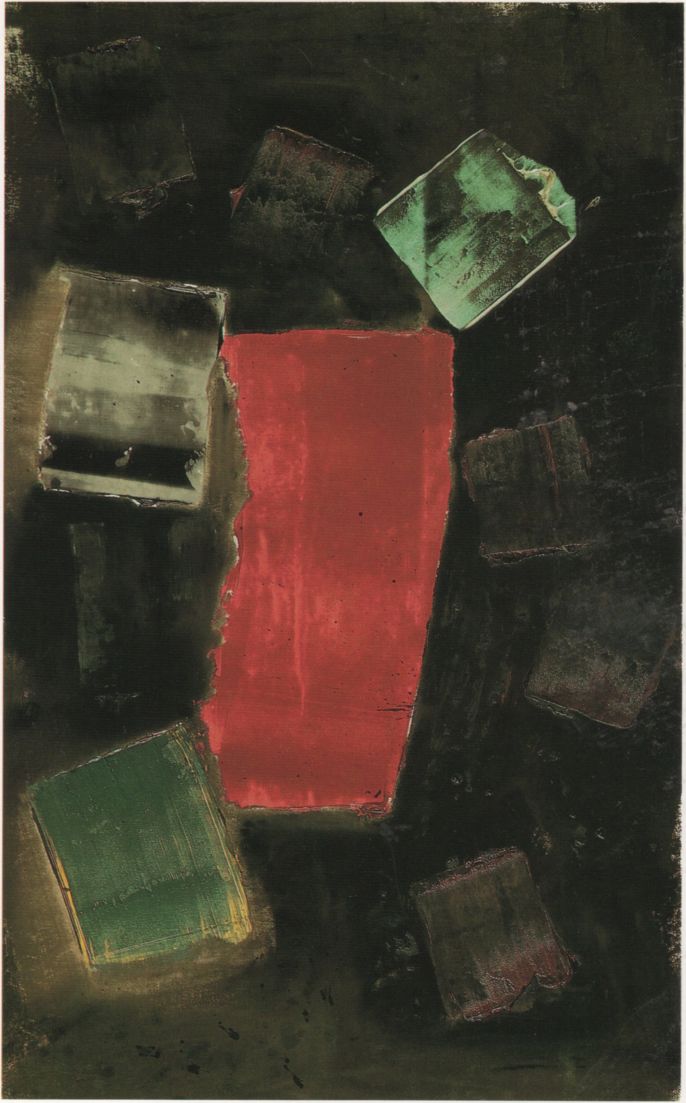

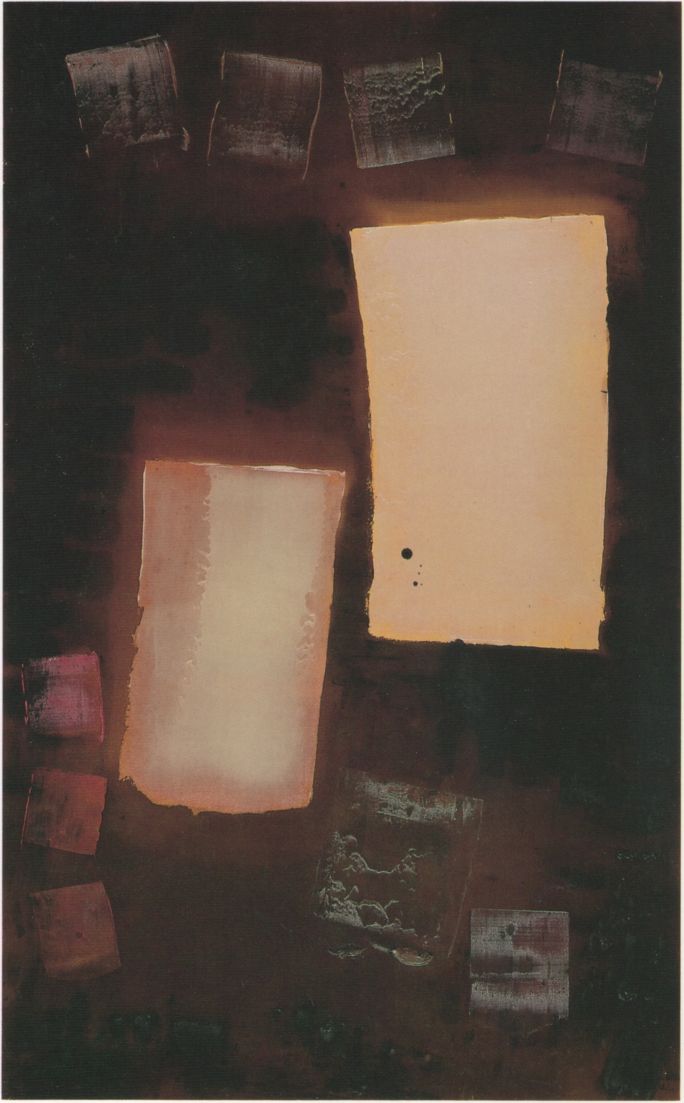

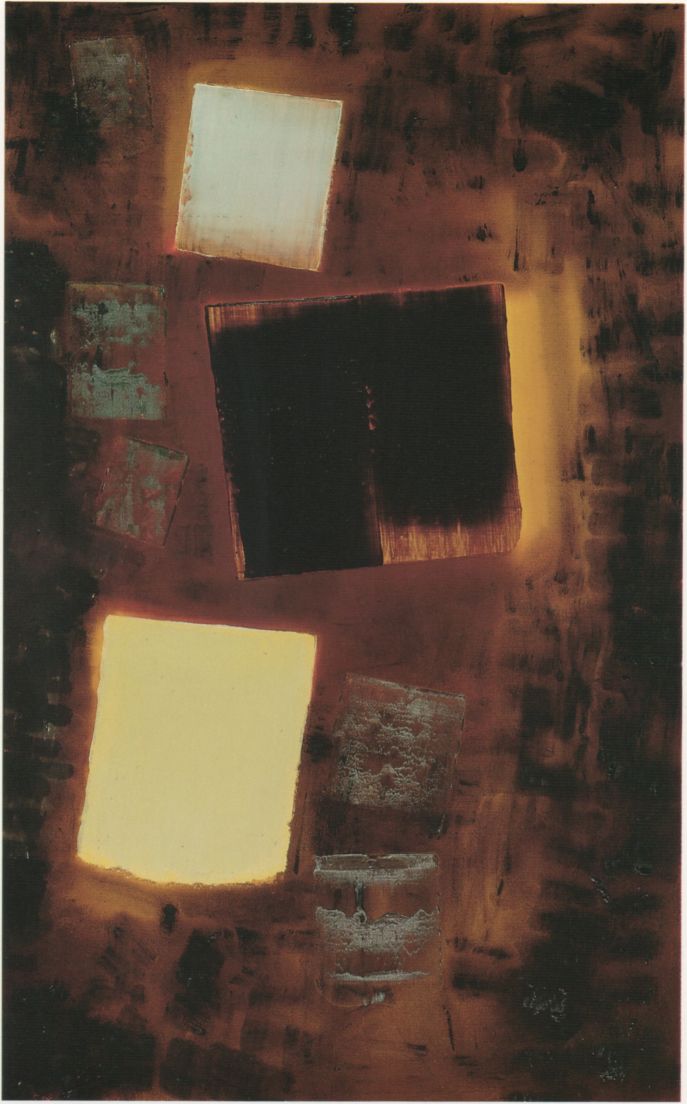

Toledo Series #1, 1988

acrylic on canvas 78 1/4" x 49 1/2"

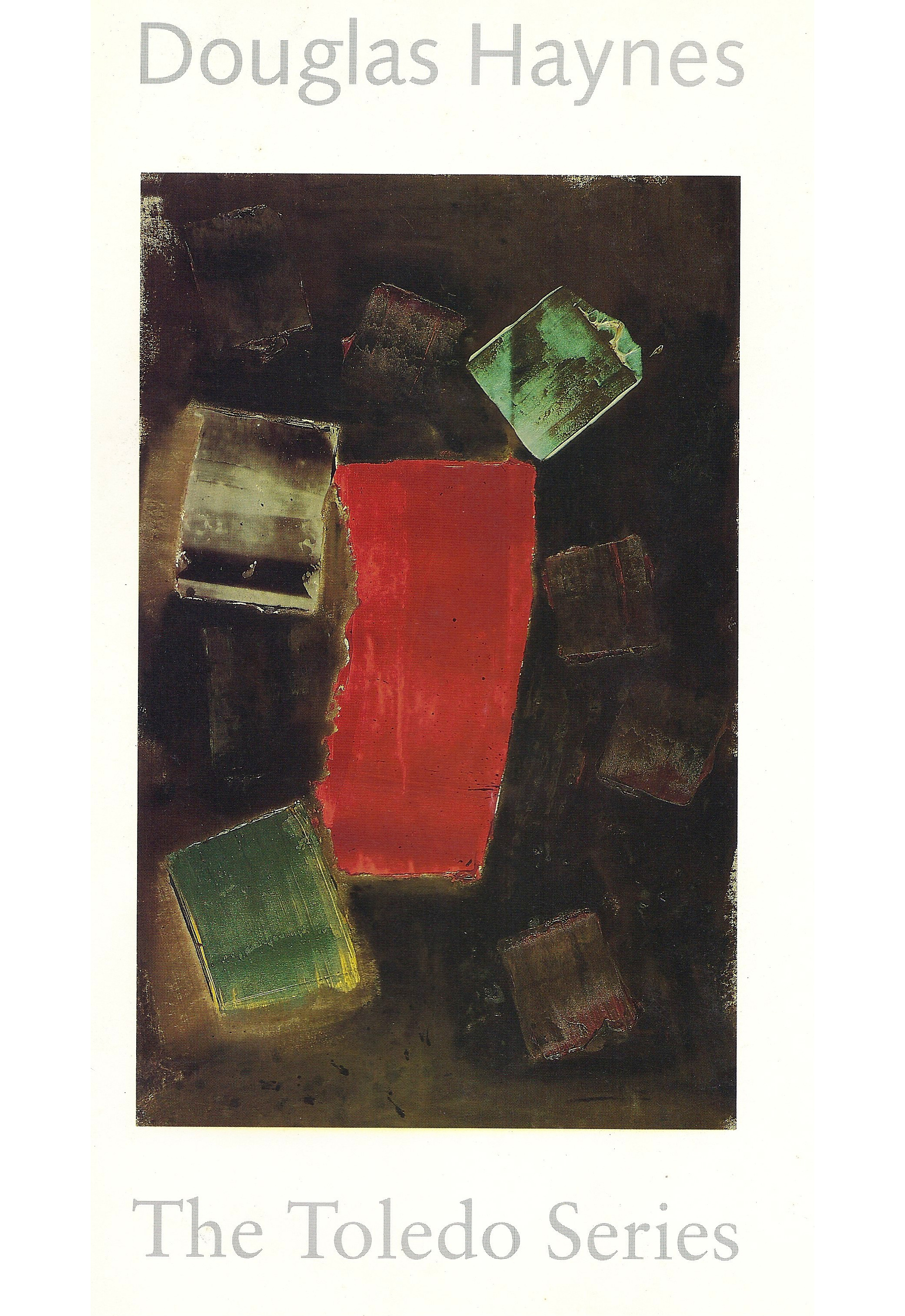

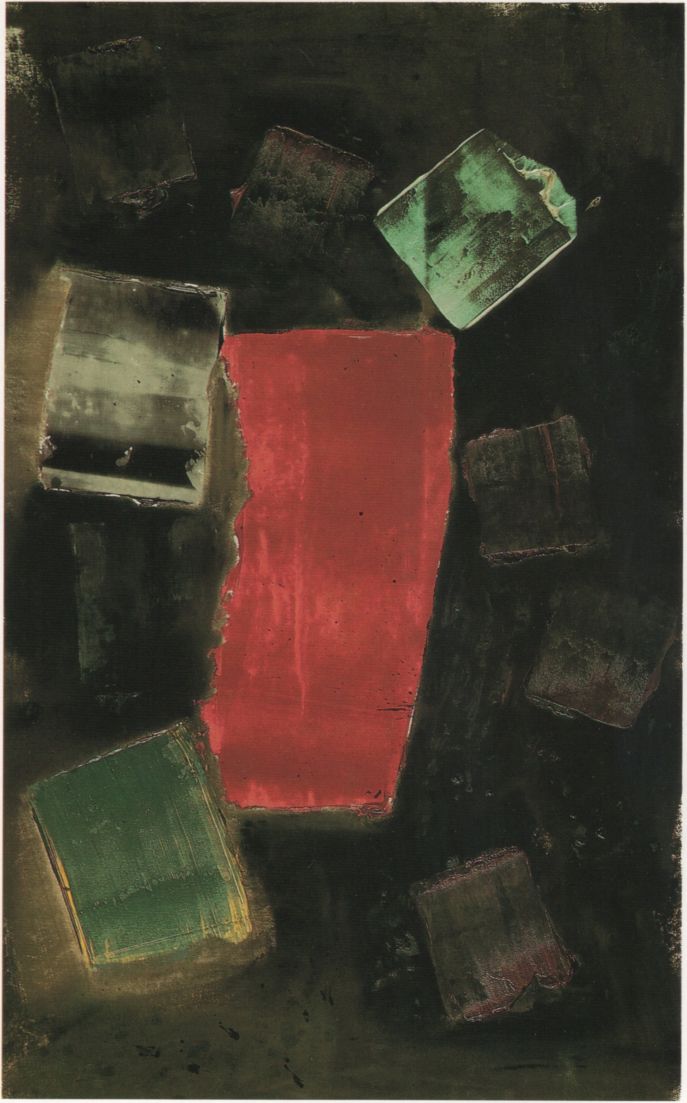

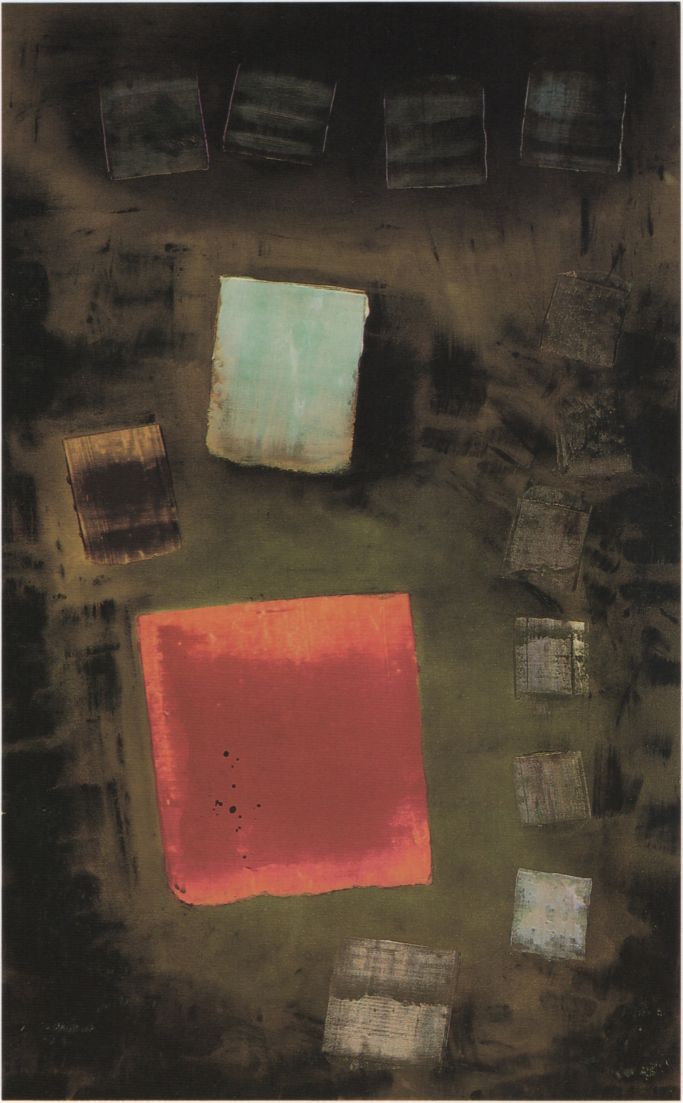

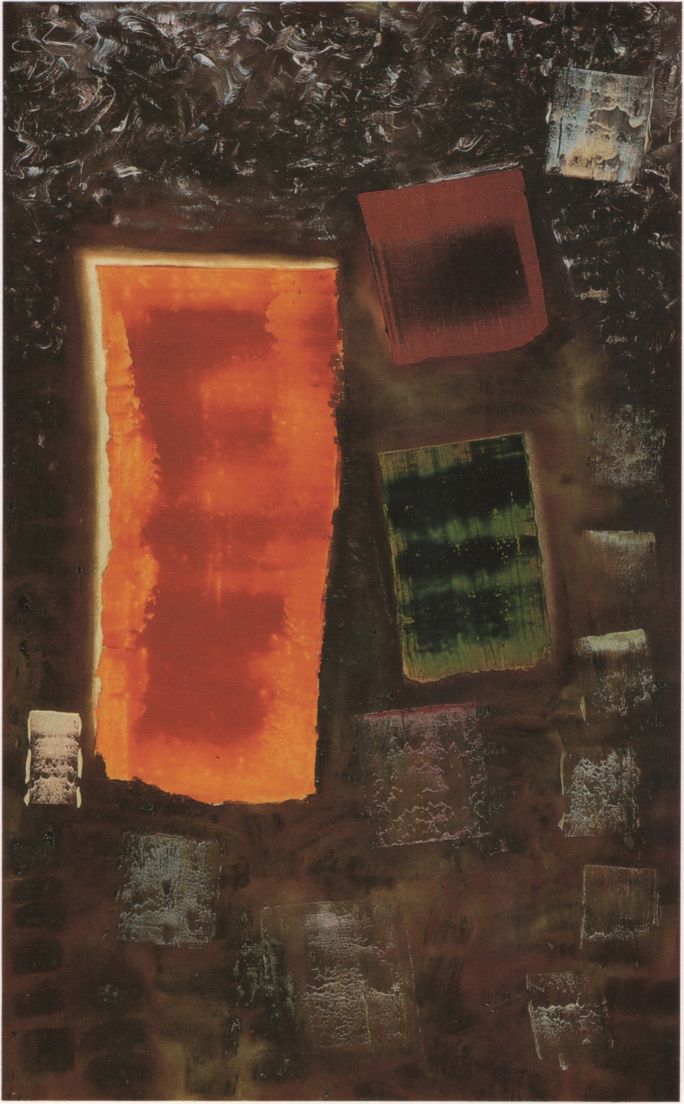

Toledo Series #7, 1988

acrylic on canvas 78 1/4" x 49 1/2"

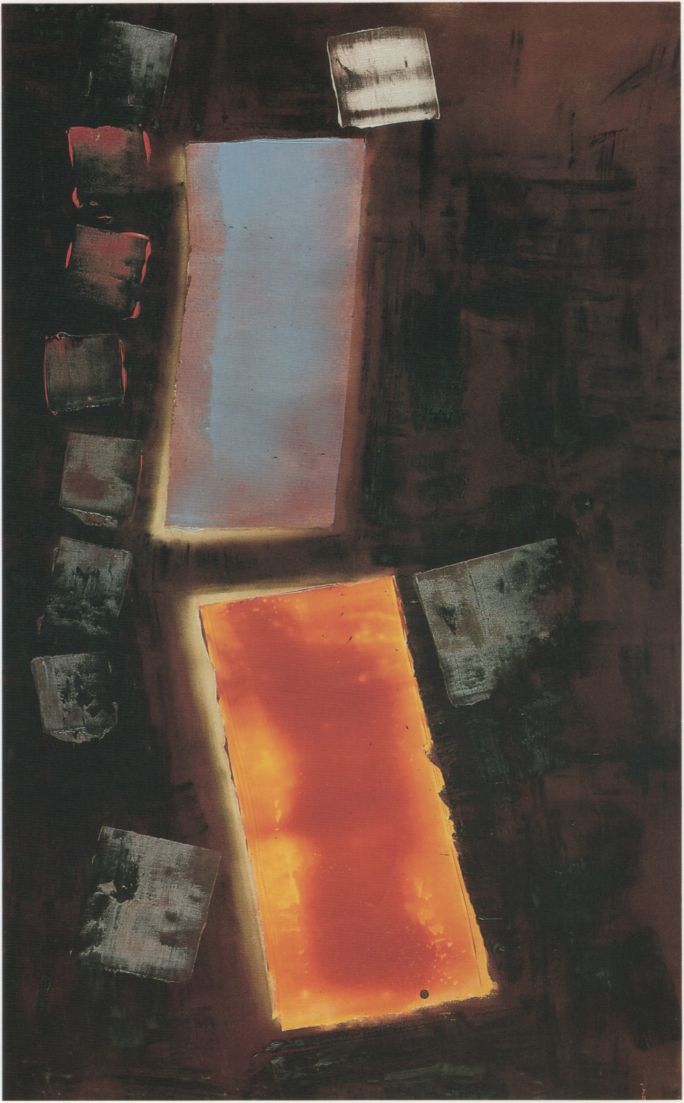

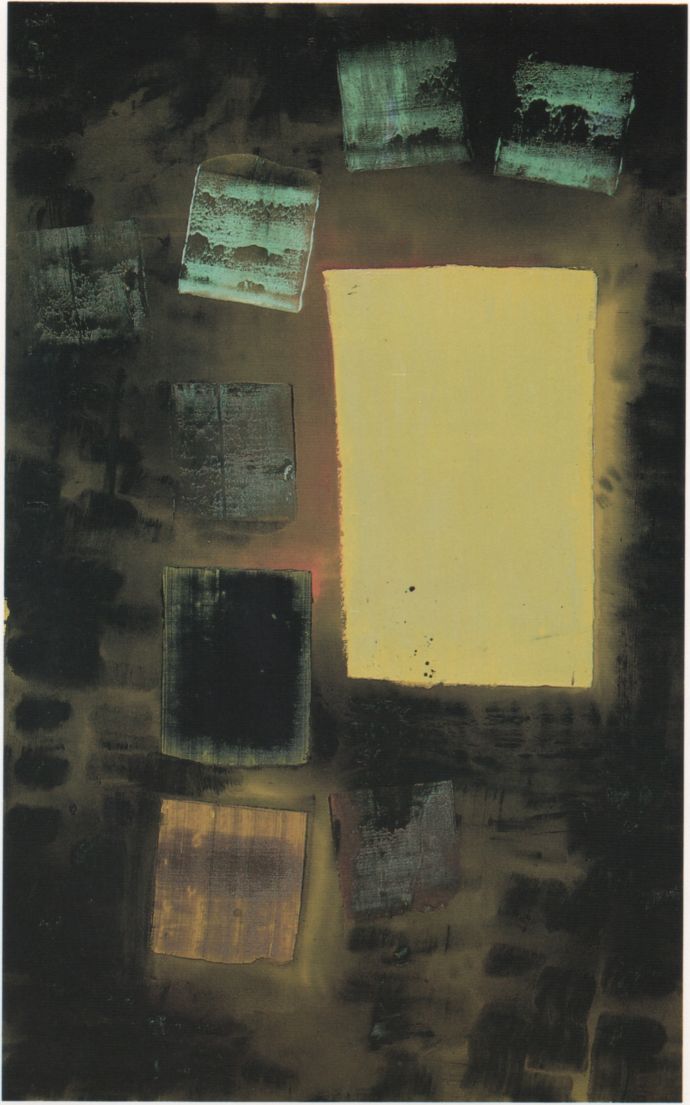

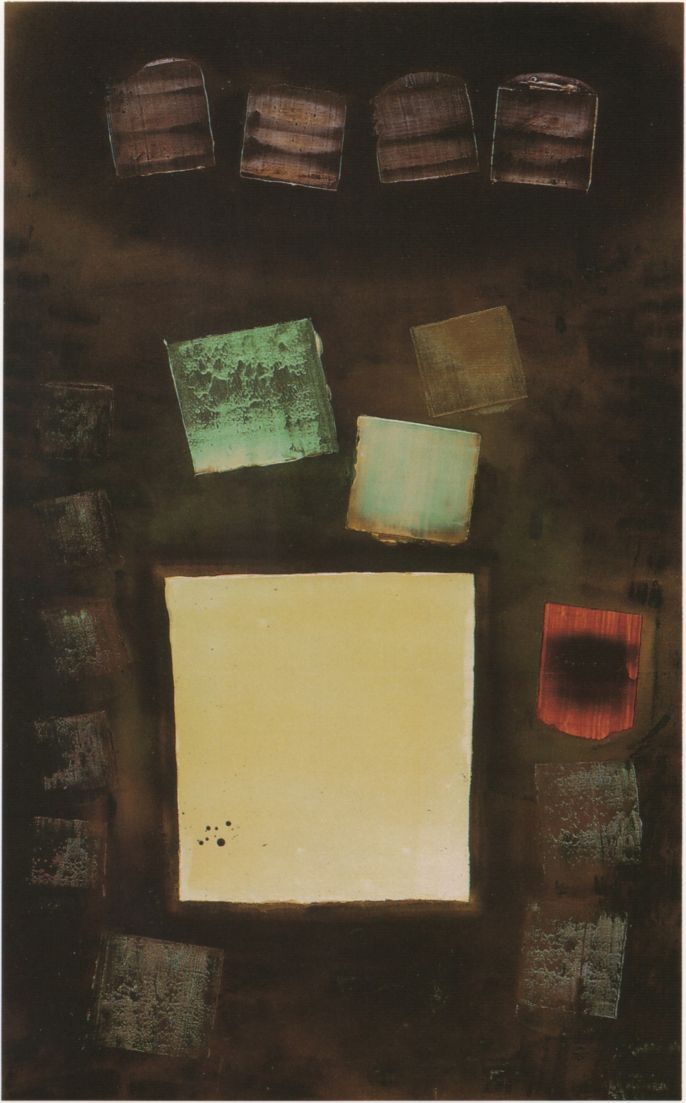

Toledo Series #5 (San Bartolome), 1989

acrylic on canvas 90 3/4” x 56 1/4"

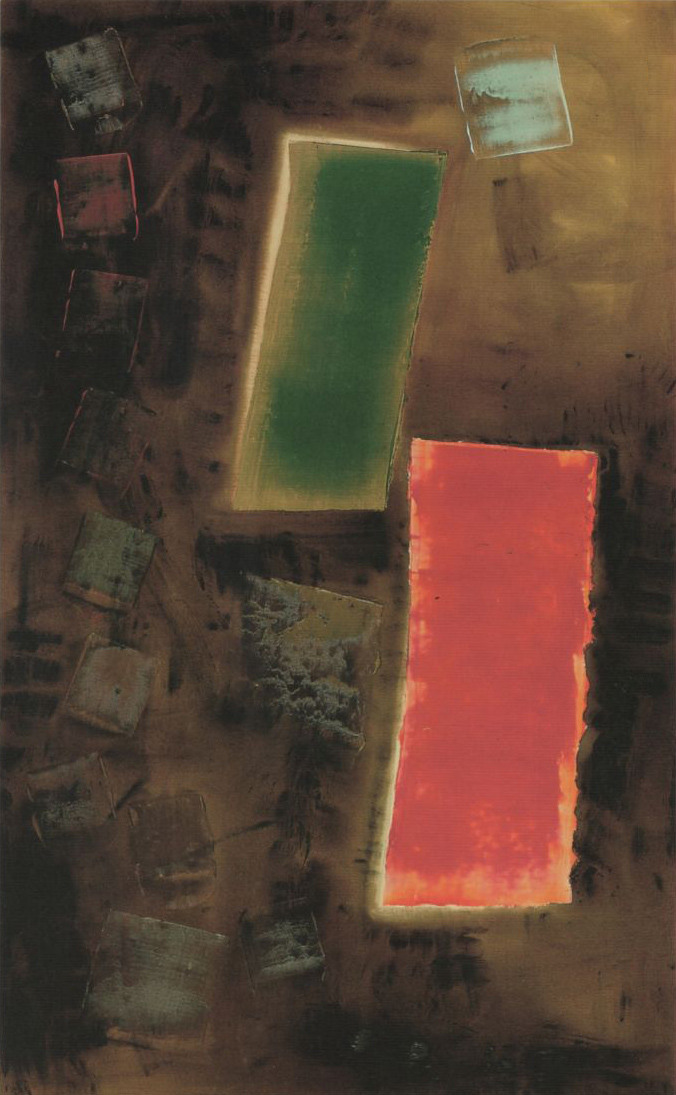

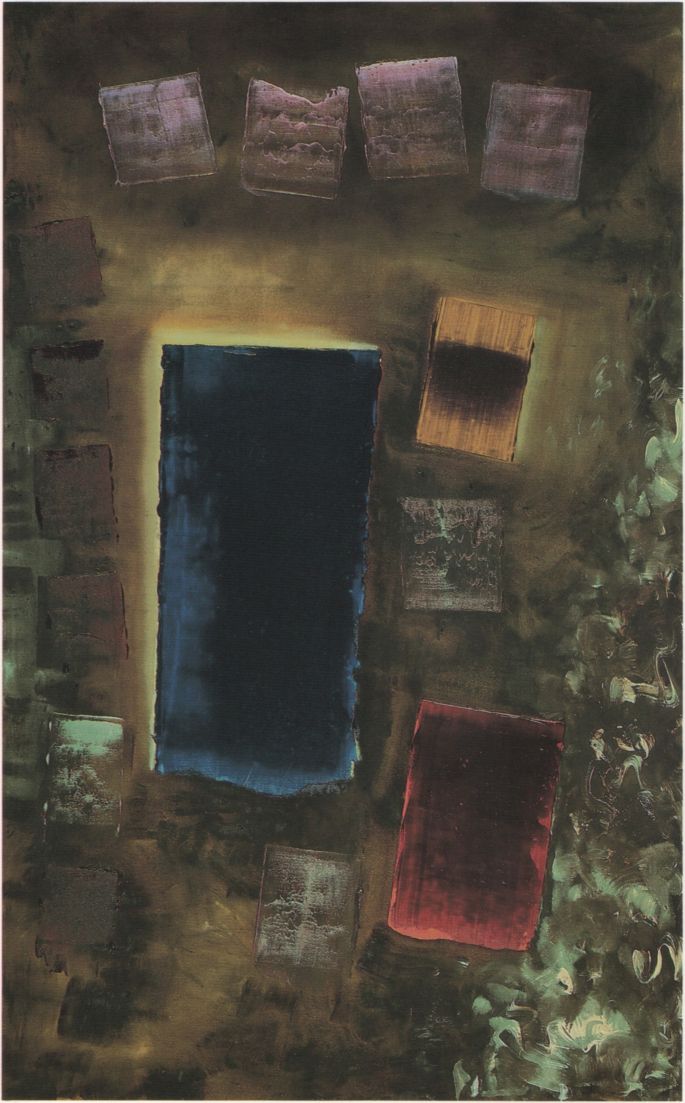

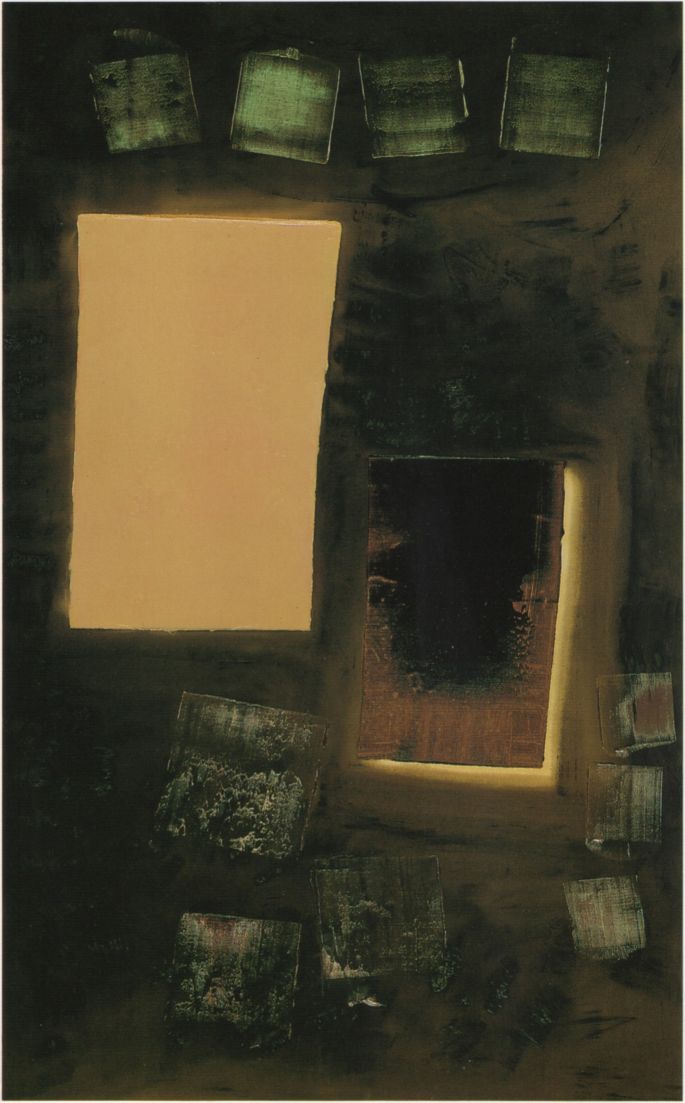

Toledo Series #8 (Santiago El Mayor), 1990

acrylic on canvas 91" x 56 1/4"

Toledo Series #7 7 (San Pedro), 1990

acrylic on canvas 90 1/2" x 56 1/4"

Toledo Series #72 (San Lucas), 1990

acrylic on canvas 90 3/4" x 56 1/4"

Toledo Series #13 (San Juan), 1990

acrylic on canvas 90 1/2" x 56 1/4"