El Greco

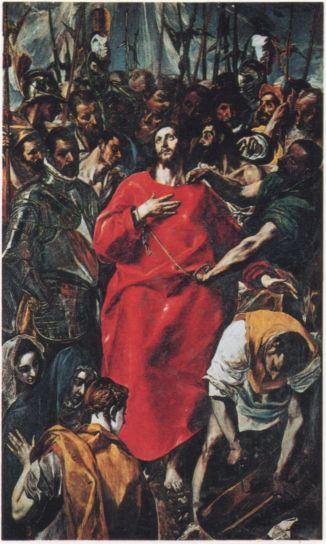

El Espolio (Disrobing of Christ), c. 1577 - 79

oil on canvas 112” x 68.1"

For nearly three years, Douglas Haynes has been at work on his Toledo Series, a group of pictures more or less directly inspired (or more accurately, provoked) by the paintings of El Greco. This exhibition consists of thirteen canvases from this slowly evolving commentary on the Spanish master, chosen to correspond roughly with the thirteen El Grecos in the sacristy of the Cathedral of Toledo that are Haynes’ sources: El Espolio, the disrobing of Christ, and Los Apostolados, twelve half-length “portraits” of the apostles.

Haynes’ Toledo Series bears witness to the intensity of his response to El Greco and to the singlemindedness of his preoccupations, yet he began these works almost casually, only to be surprised by the depth of his engagement. He was surprised, too, I think, by the fact that it was El Greco, the painter of nervous dramas lit by flickering light, who was prodding him so insistently in new directions and confirming the importance of where he had already been.

In the past, the work that stimulated Haynes most was usually less overtly expressionist than that of El Greco. Adolph Gottlieb has long been one of his heros. (“I’ve always wanted to paint like Gottlieb, but I couldn’t get that feeling without painting just like Gottlieb.”) Among the Old Masters, Haynes names Poussin as having been a “big personal discovery” on one of his trips to Europe. He recalls admiring Poussin especially because “the pictures are so well set out...They are like stage sets, a finite pre-determined space....I was able to really feed off of those pictures.”

Haynes’ enthusiasm for El Greco came later, on a subsequent trip, but it didn’t affect his own work immediately. “I had seen the Grecos in the Prado and in Toledo, of course, and been very struck with them,” he says, “but I wasn’t ready for them until the summer of 1988.” Then, dissatisfied with his current paintings, he began “to work from El Espolionot, it wifuld seem, with any particular intention of exploring El Greco, but “just to get going.” It is arguable, of course, that the very characteristics of El Espolio that made it an improbable model for Haynes — its underlying agitation and contained energy, which is to say its difference from his own cool, rational work — were just what he eventually found so Compelling, but initially, at least, Haynes had no inkling that El Greco would absorb him so completely in the future.

“The picture had stayed in my mind from the trip, so it was a conscious choice to refer to it,” Haynes recalls, “but at the same time, it was rather arbitrary.” As he describes the genesis of the series: “Just prior, I was painting large pictures using lots of gel (I do work in Edmonton, after all) and a spray gun. The pictures were based on the logic of old battle pictures, with lots of movement and strong color. I never really felt comfortable with them. They were too mechanical for my taste. I didn’t like painting them; the process blocked me out. Then I did about seven paintings from El Espolio, and did what I have often done in the past — turned everything inside out, painting first what I put in last in the previous works. I immediately felt at home, painting pictures that were direct or allowed for immediate response as I worked. Just as important, the pictures came across with the presence of a portrait or figure, yet remained abstract. I found myself thinking ‘At last, I’ve painted the paintings I’ve always wanted to paint.’ At this point, I was totally plugged into El Greco.”

There is nothing remarkable about a painter’s apprenticing himself, at one remove, to earlier artists whom he admires, nor is there anything unusual in his dissecting their work for his own enlightenment or amusement. When Rubens was sent on a diplomatic mission to the Spanish court, he used the occasion to study and copy the Titians in the royal collection. Delacroix based a number of his works on Rubens’; Van Gogh unabashedly painted from reproductions of Delacroix’s compositions, explaining that this was no different than a musician performing works that he himself had not written. Picasso’s irreverent, sometimes inspired variations on Delacroix and Velazquez, among others, are well known, while Arshile Gorky described himself, during the years when he painted prismatic landscapes and Synthetic Cubist still lifes, as being “with Cezanne” and then, “with Picasso.”

These days, many artists lean increasingly on their predecessors, but their relation to their chosen archetype is quite different than Van Gogh’s — say — to Delacroix. In 1991, a description of a project like Haynes’ Toledo Series could lead us to expect that El Greco’s imagery had been used as a springboard for ironic improvisation or that it had been fragmented and forced into new, improbable contexts. Some artists of the 1980s or ’90s might have quoted Los Apostolados verbatim, analyzed them for political, sociological, or sexual subtexts, or reduced El Espolio to^. schematic quantification.

But Haynes has neither swallowed whole the works he found so fascinating in the sacristy of the Toledo Cathedral, nor has he subjected them to modish deconstruction, parody, or simulation. Neither has he rendered a traditional act of homage to a chosen exemplar. Peculiar as the notion may sound, he seems instead to have striven to acknowledge some sort of kinship with El Greco. I described Haynes’ prolonged involvement with his Toledo Series as a commentary on El Greco’s paintings; it would be truer to have called it an extended, albeit imagined, dialogue with the Spanish Mannerist.

“The reaction to El Greco,” Haynes says, “was certainly not for any reason of looking for an idea, nor for the use of a style, nor was it appropriation. It was the recognition that concerns I had for a long time, combined with all the explorations, technical and formal, found a forebear in El Greco. He had patiently been waiting for me to catch up.”

Haynes’ approach could, of course, be seen as a demonstration of unspeakable arrogance. He seems to wish not merely to emulate the paintings that engaged him so deeply, but to rival them. “My gravitation toward Poussin and El Greco is a reflection of my needs. They point the way along a path that I am already on,” Haynes says. “I didn’t go looking for them. They found me and hollered to me from across the room, and time, for that matter. It is not a case of a programmed plan of development, but rather a response to feeling of what I seem to be searching for, both in form and content.”

It’s as though Haynes hoped to reinvent El Greco in contemporary terms, to paint the pictures that Domenikos Theotokopoulos might have painted, if he had been, instead of a Venetian-trained Cretan working with oil paint in Toledo, at the turn of the sixteenth century, a visually sophisticated Canadian Abstractionist armed with the full complement of state-of-the-art acrylic paint, at the end of the twentieth century. An often-quoted

anecdote about Jack Bush may help to explain what Haynes is after. Bush, after his first European trip, spoke of how impressed he was by Matisse’s work, especially by the late, monumental papiers coupes. What he really wanted to do in his own work, he said, was “hit Matisse’s ball out of the park.” (The friend to whom he confided this told him,

“Go ahead. Matisse won’t mind at all.”)

El Greco

El Espolio (Disrobing of Christ), c. 1577 - 79

oil on canvas 112” x 68.1"

Haynes’ audacious program is less outrageous in the context of his own evolution. Although he is known as an abstract painter, and one with a thoroughly modernist faith in both the expressive potential of materials and the inherent expressiveness of the act of painting, he has always been engaged in some kind of dialogue with the past. (Dedicated to abstraction almost from the start, he nonetheless longed for qualities in his abstract painting that he associated with the art of the past.) His statement about “feeding off of Poussin” is typical. For all Haynes’ apparent celebration of modern-day materials and his evocation of wordless emotional states, the pictures that immediately preceded the Toledo paintings were often loosely based on the compositional strategies of traditional narrative painting. Even earlier, from the mid-’80s on, Haynes was “with Cubism,” in the way that Gorky was “with Cezanne,” producing fine, large-scale paintings that were wholly personal but deeply informed by Picasso’s and Braque’s explorations of the Analytic Cubist years.

As in the Toledo Series, the self-declared apprentice was not content simply to follow his masters. Haynes’ “Cubist” pictures do not so much imitate the iconographic and formal vocabulary, the palette and the spatial inventions of Braque and Picasso, as they interpret them in terms that are completely of the 1980s. The small, transparent, delicately shaded planes that, in Analytic Cubist works, result from meticulous touches of the brush, are reinvented by Haynes as large-scale swipes of a paint-spreading tool that literally interrupts the surface. These thick and thin zones of acrylic paint, with its varying translucency, at once allude to the appearance of transparent Cubist planes and to their fictive role as components of a new, constructed reality. Haynes’ “translations” of Cubist images are not only very beautiful pictures, but pose challenging questions about illusion and materiality, and perhaps even more challenging questions about the contemporary painter’s relation to his intellectual inheritance.

Haynes has been wrestling with these questions for much of his life as a painter. From the late 1970s on, Haynes says he was particularly occupied with “the notion of painting as portrait.” In 1979, he wrote in a notebook: “I think it has something to do with recapturing the sense of image for abstract painting. By image, I mean something different from motif...a kind of holistic, self-contained image like the portraits of the masters....To date, no one has painted such an image, resolutely abstract, that allows the color spread of Noland, with the paint handling of Olitski, and ended up with a portrait, or personality.”

When he made this entry, Haynes was painting the series known as Split-Diamonds, the works that now appear to have signalled his maturity as a painter. (He says he thinks of them as “my first grown-up pictures.”) The Split-Diamonds were notable for the way their over-scaled, “winged” images flew straight at the viewer, barely contained by their richly colored, subtly inflected grounds, demanding to be acknowledged. Haynes says he thought a great deal about the individual character of each of these paintings. “I would keep working on them until they achieved a personality, often going through three or four until one felt right. This portrait idea carried on more or less until I ran into Cubism.”

Haynes set his preoccupation with “the portrait” aside when he began his Cubist-derived series, largely because of the still life associations of their prototypes. But the Toledo Series had figurative antecedents, and as Haynes describes it, “When I encountered the Espolio pictures...back came the portrait/personality concern.”

The proximity of El Espolio to the twelve Apostolados, in the sacristy, suggested to Haynes a way of intensifying that concern and making it more explicit. Without compromising abstractness, he began to think of each canvas as a portrait. “It was a small step to put it together with the logic of a group of twelve. Technical issues aside, which had been simplified greatly, all I had to do was think of one-liners, such as ‘I suppose one would be snarly, another more gentle.’ Well, maybe it was a little more complex. I had to paint about sixty-five of them to get the twelve. Halfway through all these paintings, I mentioned to my sculptor-friend A1 Reynolds that getting twelve of equal quality was more difficult than I anticipated. A1 remarked, ‘Well, you know,

Christ probably didn’t take the first twelve that came along.’”

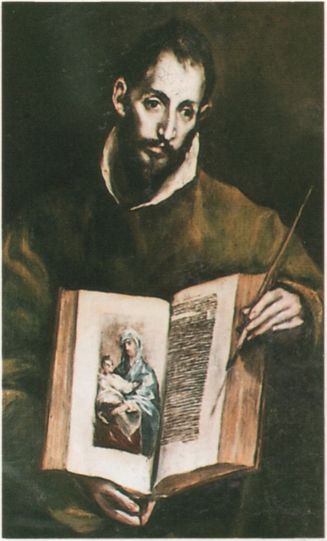

Which brings us to the two key questions about Haynes’ Toledo Series. First: what is the specific relation of the thirteen canvases in this exhibition to El Espolio and Los Apostolados? Second: must we consider “spiritual” content in a group of paintings made in a secular context, not to satisfy the demands of a militant Counter-Reformation church, but to respond to an artist’s self-imposed aesthetic demands? The first issue is relatively simple. There is no one-to-one relationship between any of Haynes’ pictures and those of El Greco. It’s evident that each of the Toledo pictures has an individual mood, but it doesn’t correspond directly to any of the Apostolados. “At first,” Haynes says, “they were more directly based on the apostles. Luke holds a big book and that led to a painting with a big center square. Originally, the disposition of blocks of color came out of the disposition of colors of the Apostolados, but that was only a way of getting started. After a while, I forgot about it.”

Even if we didn’t know about Haynes’ fascination with El Espolio and Los Apostolados, the Toledo Series paintings would still have powerful associations with Mannerist and early Baroque painting, because of their color and light. But if we are looking for simple parallels with El Greco’s work — updated versions of elongated, flame-like shapes, tremulous drawing or agitated compositions — we will be

El Greco

San Lucas c. 1605-10

oil on canvas 39 x 29"

disappointed. Haynes clearly responds to the expressionist drama and the passion of the Spanish master’s pictures, but he values him for other reasons as well. He has, for example, praised El Greco for the same inevitability and finiteness of composition that he admires in Poussin. This is not to say that the Toledo Series lacks drama, or that Haynes’ means of achieving it differs greatly from El Greco’s.

There is no explicit narrative in the Toledo Series to engage our feelings, but emotional intensity results from the way darks are penetrated by light and the way bright color pulls itself free of glowing darkness and pulses forward, just as it does in El Espolio and Los Apostolados. The disposition and relative sizes of color blocks produce subtle spatial illusions, as ambiguous in their way as the unstable Mannerist spaces of El Greco’s paintings.

But no matter how potent their evocation of the past, how sumptuous and “Old Master-ish” their color, the works in the Toledo Series are not stripped down, disguised versions of earlier art. Rather, they are new inventions that aspire to achieve the emotional impact of earlier art within the formal and technical language of the late twentieth century. These pictures bear eloquent witness to the history of their making. They are, after all, not depictions of imagined persons or events, but material objects whose meaning resides in inflections of surface, clashes and accords of color, tensions between parts. The physical character of each block — its transparency or opacity, its color and relative size, its four-squareness or deformation — helps to create the sense of personality and animation that dominates each canvas, not any presumed echo of one of El Greco’s images of high drama. Haynes is well aware of this. “It was the response to materials that led me to El Greco,” he says, “not the other way around. But what I didn’t realize until I went back to Madrid and Toledo, was how similar the painting methods are. El Greco used a red ground, with lights on top, leaving the rest dark. I’m doing the same thing. It’s different because it’s acrylic, but it is the same kind of layering of brights over lights, brushing over.”

When Haynes speaks of El Greco’s paintings (or anyone else’s, for that matter), he concentrates on what is there before him, what can be seen and verified. After one of his trips to Spain, Haynes reported on the paintings of El Greco at the Prado to his friend, Harold Feist: “There is very little reference to the real world, no buildings or vista-like landscape stretching out behind and across. Hence you don’t feel you are looking at a cropped event from the real world, but rather at a dream-like abstracted world complete unto itself. The pictures really are remarkable. Most of the space described is the negative space, such as that described between the outstretched hands of one of the figures, as though he was holding an invisible balloon, or the space captured between the wings of the angels. At times, the clouds are like rocks and the figures like wraiths, a curious turning of things inside out that keeps the whole space forever turning back on itself.” Substitute “color blocks” or “planes” for “figures” or “clouds” and you have a useful description of how Haynes’ apostle pictures function.

Not surprisingly, Haynes interrogates the work of the Old Masters he admires from the point of view of a mature, thoughtful modernist painter who both accepts and questions fundamental assumptions about the canvas as an autonomous, flat plane. He seems both to seek confirmation of these ideas and to challenge them.'Recently, he wrote, after seeing a major Titian exhibition: “The painting seems to bulge and give, but never bursts or breaks, and so retains a tenuous tension across the surface, a formal drama that charges the theatrical feeling of the light. Like playing on a drum, it gives when hit, bends a little and bounces back...perspective pushing and painting pulling. How in the world can people not be excited by the formal properties of painting? It’s drama!”

This kind of detached, albeit passionate formal analysis notwithstanding, Haynes’

Toledo Series is a response to a group of devotional paintings, not of court portraits, battle or genre scenes, so the question of religious or spiritual content inevitably arises. Pressed, Haynes says that thinking about each of the apostles as an individual personality, while he was painting the series, added “another dimension” to what he was doing. “And because it was the apostles, it got me thinking in a religious way, not in any Catholic sense, but in a general spiritual sense.” But, it seems, spiritual thinking and the sensuous materiality of paint and process are inextricably bound together, for Haynes. The small, floating shapes in the periphery of some of his “apostle” pictures are, he says, freely derived from El Greco’s angels. “I thought,” he says, “if they’re angels, they can be ethereal. That’s good use of interference paint!”

It is impossible, I think, to separate the potent emotional charge of Haynes’ Toledo Series from their equally potent material presence. The pictures seem to happen as we look at them, their glowing blocks of color, as compelling as any image of a Mannerist saint, momentarily floating to the surface of the palpable darkness they inhabit, trailing halos of light. Haynes’ religious convictions are, of course, a private matter, and for viewers of the Toledo Series, they remain a matter of conjecture only — as do El Greco’s, who produced, on demand, images faithful to the official church doctrine of the period, not personal interpretations of the New Testament. Yet El Greco’s subject matter is unequivocal. In Haynes’ work, I suspect that without the apostolic titles, the issue of specific spiritual content might not arise. What does come through, unequivocally, is his passion for painting, in all its aspects, as observer, participant, innovator and member of a long tradition. It is as if Haynes had found a way of making visible the excitement he felt when making his pictures, substituting the exhilaration, doubt, puzzlement, and pleasure of the act of making art for the religious dogma of El Greco’s day. Haynes’ Toledo Series can be read as a modern day pantheon, an Apostolados of the act of painting.

Haynes himself has said it best: “I find myself reacting to pictures like Titian’s and El Greco’s as if they are angels revisiting, messengers bearing truth, virtue, and equality — what painting can be.”

Karen Wilkin New York, 1991